Establishing the New Italy settlement

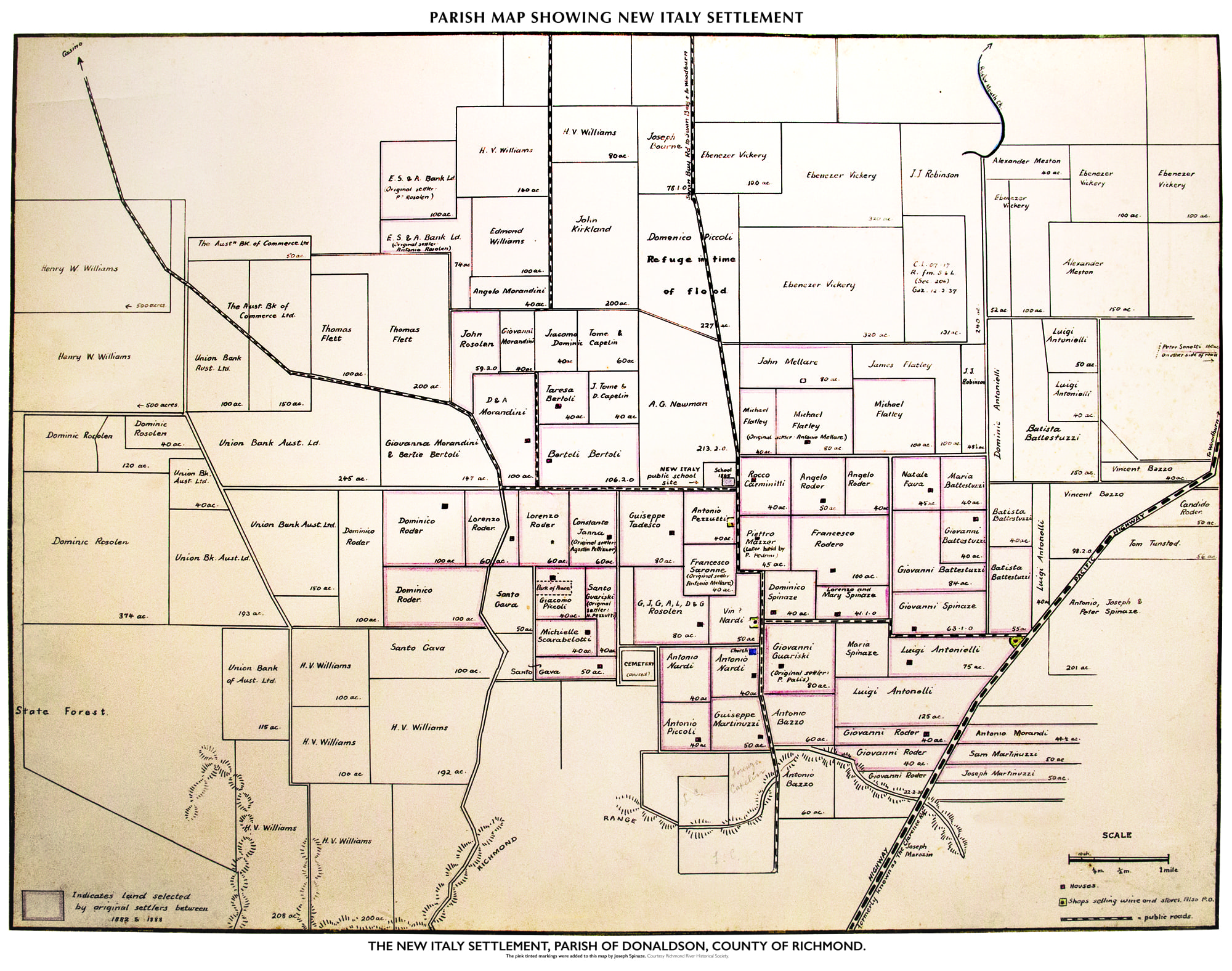

It was just over one year following their arrival in Sydney Harbour, after fulfilling Henry Parkes’ decree to work amongst the colonies of New South Wales, when expedition families were introduced to land in the Richmond River Valley. The northern Rivers was the last region in the colony still available for selection, and this was ‘left over’ land that other colonists had rejected. The 19th century observer of New Italy, Frederick Clifford, calculated that 3,030 acres was taken up by 34 Italian families between 1882 and 1888. They had been joined by other Italians, who were not expedition survivors. By 1887 the settlement numbered 202 people, (99 adults, and 103 children under 16).

The Italians brought their agricultural traditions and practices from their homeland. Unlike the broad-scale agriculture of surrounding properties, they intensively farmed small, agricultural plots of vegetables and some crops, developed orchards and planted vineyards with cuttings they brought from Italy. They kept pigs for salami making, house cows, and poultry. However, the soil for cropping was barren and the first years were very hard.

Members of the New Italy Settlement. Photographer Joseph Check c1896

Reproduced with permission of CoAslt – Italian Historical Society: courtesy State Library NSW

Reflecting on his first visit, Clifford noted: Italians toiled from sunrise until dark. Men, women and children were either using hoe or axe. The land was poor. No spread of ink could overcome its poverty, or keep the stock alive. Of the few cows and horses bought with the earnings made at sleeper-making or sugar cane cutting, many have died during the last two years.

It was Rocco Caminiti, a fellow Italian, who first alerted the Marquis de Ray survivors of available land in Northern New South Wales. Antonio Pezzutti, Pietro Mazzer and he, selected the first blocks. Rocco married Catherina Gala, whose father Giovanni had died in Port Breton.

Free Selection: land tenure in colonial New South Wales

Title to land in colonial New South Wales required that settlers build, and live, on their property. So the New Italy settlement was spread across the landscape rather than forming a tight village structure. From here it was 4 km to the next cluster of buildings – the Catholic Church, the Nardis’ wine, shop and community hall. 2 km further on stood the school and the Pezzutti/Pedrini post office and store/wine shop.

As the settlers began leaving New Italy in increasing numbers from the early 1900s, they dismantled and rebuilt dwellings on their next properties. The church blew down in a cyclone and the deserted pise homes eventually crumble back into the earth. Nothing remains to be seen of any of the buildings.

The Crown Lands Acts of 1861, also known as the Robertson Land Acts, open public, (Crown) lands in designated regions for the selection of small-scale farming blocks between 40 and 320 acres. Until that time landed been ‘locked up’ under the vast leases of the squatters. ‘Free Selection’ meant the ability for those little capital to purchase unsurveyed land at 1 pound per acre, under a deposit.

The balance of the purchase was meant to be paid to the government treasurer after three years. However, in practice, payments could be made annually at 5% interest. It often took between 20 and 30 years before freehold title to the land was eventually granted. All the original land at New Italy was purchased through this process.

<< (8) Pioneer Kitchen