Sericulture at New Italy

SILK: THE PROMISES AND FAILURE OF AN INDEPENDENT INDUSTRY AT NEW ITALY

At the end of the nineteenth century the premier, Sir Henry Parkes, was keen to initiate new industries in northern New South Wales. When Reginald Champ proposed the establishment of sericulture or silk farming in the colony, Parkes remembered the Italian settlers and sent him to New Italy. The settlers were keen to find an industry that would enable everyone to stay at home, instead of the men having to spend months working away to provide an income. They sent a petition to Parkes in 1890 assuring him of their willingness and ability to establish such an enterprise.

Champ was appointed official advisor to the settlement in early 1891, and for the next two years the breeding of silkworms became a major activity. Land was cleared for mulberry trees and loans to sixteen families totalling 608 pounds were received. More was promised.

Henry Parkes lost office in October 1891. While far less supportive, the new Dibbs government nevertheless commissioned Director of Agriculture, Walter Campbell, to visit New Italy in 1892 and report on the tentative industry. He noted Parkes’ reasons for choosing the settlement:

It was in consequence of the experience and knowledge gained by the Italians in sericulture at their native county of Venetia, in Italy, and the fact that the mulberry flourished in the district, that the late Governor decided to aid and encourage the industry here. This, then, is the first attempt that has ever been made by the State, to introduce, in a practical manner, the silk industry in New South Wales.

Campbell seemed delighted with the scenes that met him, describing the silkworms being reared in all sorts of places: ‘kitchens, bedrooms, sheds, anywhere under some sort of cover: the little houses were crowded with silkworms in all sorts of contrivances for trays.’ He found that most of the men were still away working, but the knowledge and skills of the women impressed him:

Anyone would see at a glance that the women were very expert in managing the worms. They seemed to be delighted to get to the business to which they had been brought up to again; and they took the keenest interest in the silkworms, which they treated quite like pets.

When starting his advisor’s role to New Italy, Champ had reported it was ‘under very discouraging circumstances’. Public opinion about the settlement’s silk industry ‘was altogether against him’. But two years on, Campbell observed that the success of the initial experiments at New Italy had created great interest in the region, and he now found enthusiastic support for the Italians. Raw silk produced by Mrs Piccoli (Snr) from a ‘first production at New Italy’ was sent to Sydney in 1892 and accepted for the 1893 International Exhibition in Chicago, winning an award.

However, the dreams for a sustainable industry at home in New Italy were not destined to be. Drought and Depression descended across New South Wales. The government withdrew all its support for the venture. Most of the mulberry trees died in the drought and a devastating fire swept through the settlement in 1893. Silk production as a large-scale, government sponsored industry, ended abruptly.

Small scale production continued among a few. Returning from his years of travel abroad, Giacomo Piccoli became the famed silk producer at New Italy. He won awards at the 1899 Sydney Exhibition and at Milan in 1906 for his silk.

Alongside the award (above), New Italy won awards at the international exhibitions of Chicago 1893 and Milan 1906

Giacomo Piccoli on his return from overseas travels

The Piccoli family harvesting silkworm cocoons at New Italy in 1899

Processing the silkworms and spinning the silk.

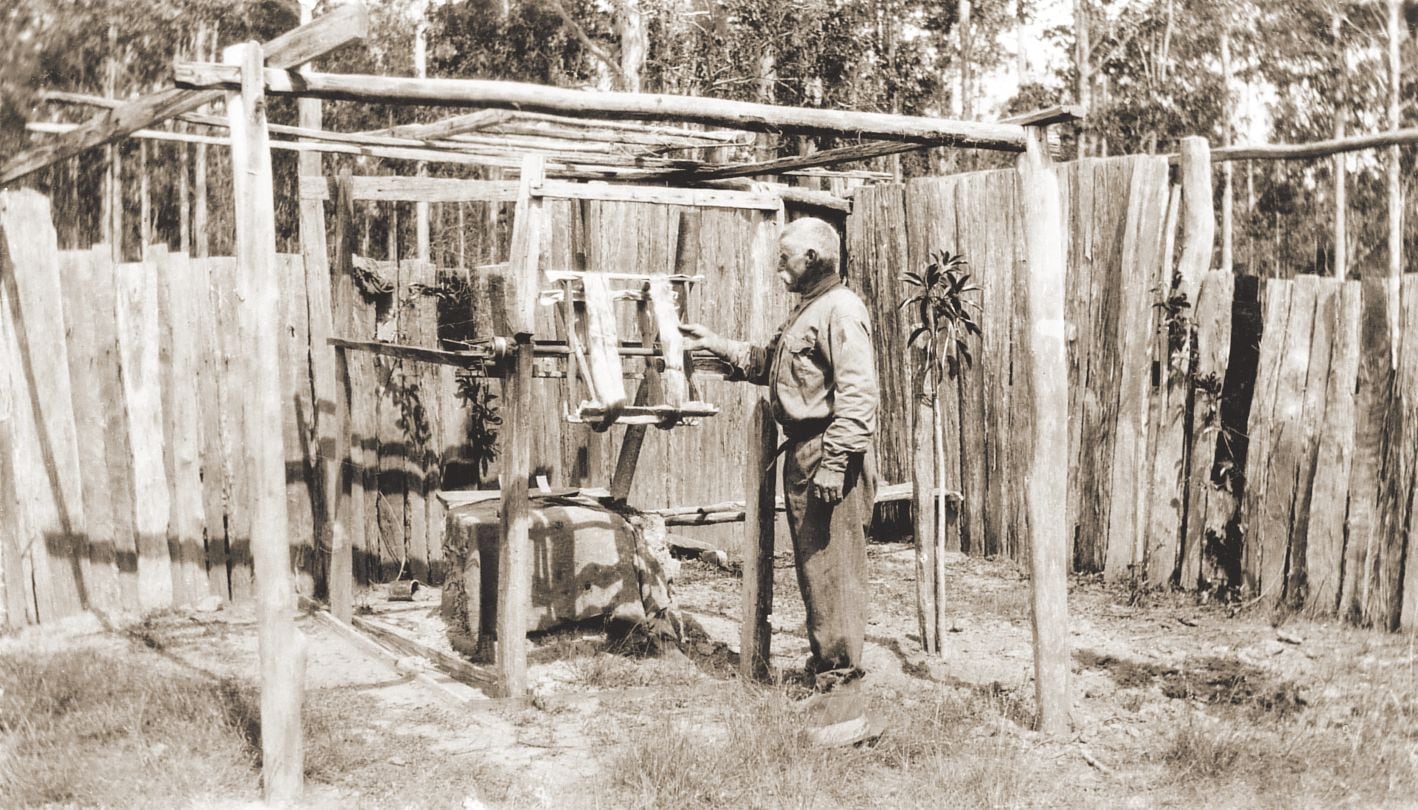

Giacomo Piccoli in later years spinning silk.

SERICULTURE

The production of silk involves:

a. The care of the domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori) from the egg stage through to the completion of the cocoon and

b. The production of mulberry trees that provide leaves for the silkworms to eat.

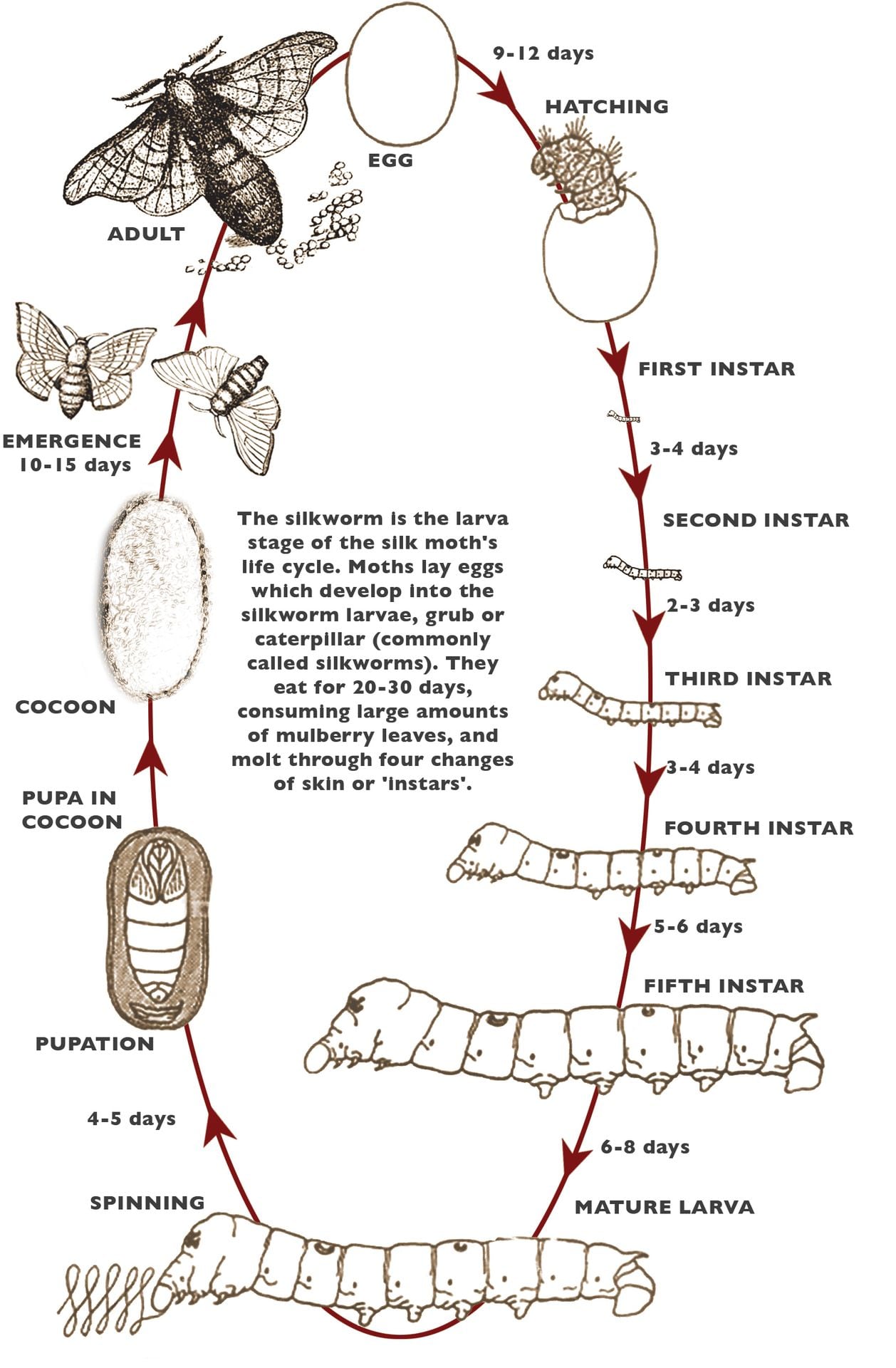

The “silkworm” is not a worm but the moth larvae of the Bombyx mori moth larvae.

1. HATCHING THE EGGS

The first stage of silk production is the laying of the silkworm egg. One female moth will lay between 300 to 400 eggs at a time, each the size of a pinhead. Immediately afterwards the female moth dies followed by the male moth. The tiny eggs of the silkworm moth hatch into larvae or caterpillars after 10 days. At this point, each larva is about 6 millimetres long.

2. THE FEEDING PERIOD

Once hatched, the larvae are placed in a dry, warm and undisturbed place and fed huge amounts of mulberry leaves. During this time, they shed their skin four times. Larvae fed on mulberry leaves produce the very finest silk. Each larva will eat 50,000 times its initial weight in plant material.

For about six weeks the silkworm eats continually. At around 6 weeks, they will have grown to a maximum size of about 7 centimetres and are about 10,000 times heavier than when it hatched. They stop eating and change colour. The silkworm is now ready to spin a silk cocoon.

3. SPINNING THE COCOON

The silkworm attaches itself to a frame, a twig, or a shrub in a rearing house to spin a silk cocoon over a 3 to 8 day period. This period is called pupating. Steadily over the next four days, the silkworm rotates its body in a figure-8 movement around 300,000 times, constructing a cocoon and producing about a kilometre of silk filament.

4. REELING THE FILAMENT

At this stage, the cocoon is treated with hot air or steam. Because an emerging moth would break the cocoon filament, the larva is killed in the cocoon at the chrysalis stage. The silk is then unbound from the cocoon by softening the sericin and then delicately and carefully unwinding, or ‘reeling’ the filaments from 4 – 8 cocoons at once, sometimes with a slight twist, to create a single strand.

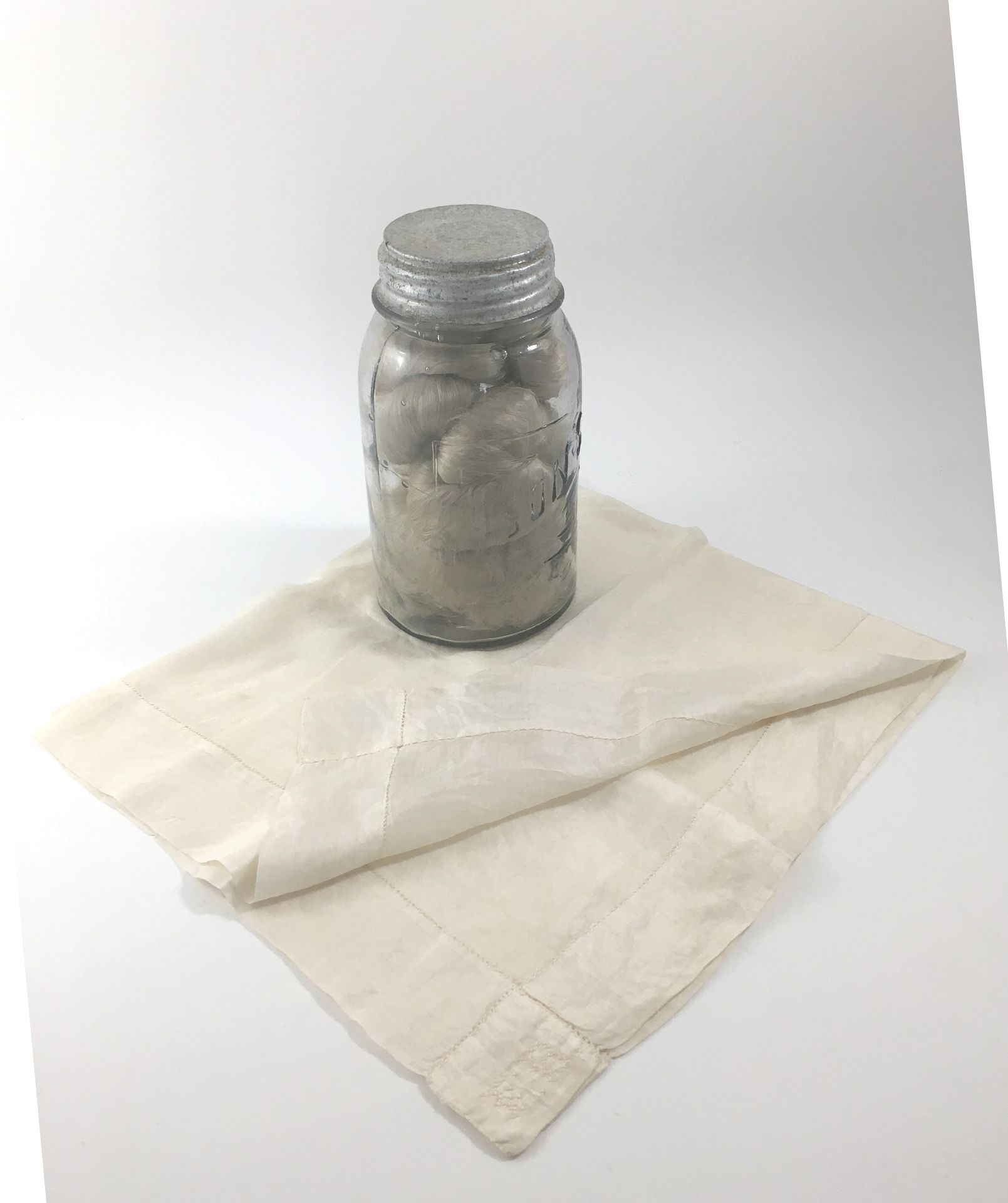

As the sericin protects the silk fibre during processing, this is often left in until the yarn or even woven fabric stage. Raw silk is silk that contains sericin. Once this is washed out (in soap and boiling water), the fabric is left soft, lustrous, and up to 30% lighter. The amount of usable silk in each cocoon is small, and about 5000 silkworms are required to produce a kilo of raw silk.

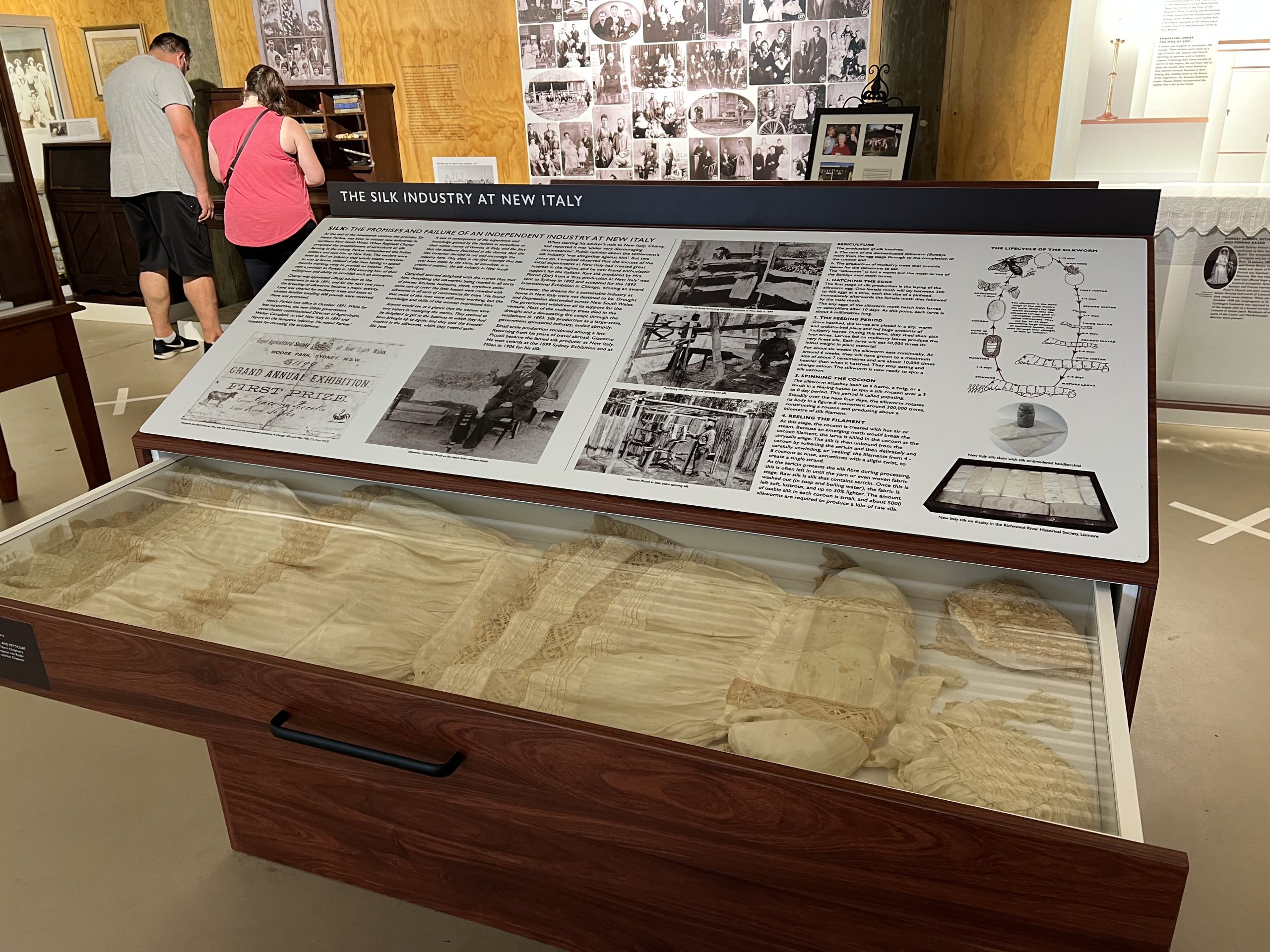

New Italy Silk: skein with silk embroidered handkerchief

New Italy silk on display in the Richmond River Historical Society, Lismore.

Dreams of Silk – Silkworms were originally tamed in China and are now so domesticated that they cannot even hang onto the leaves of their food plant, but have to be kept in cages and have food leaves given to them. The tale of their domestication is part Chinese Folklore. Silkworms were introduced by European settlers into Australia in the nineteenth century. Attempts are still being made to set up a Sericulture industry in Australia. Australian environmental conditions are very suitable for the development of sericulture industry including silkworm rearing and cultivation of mulberry plants. This had been recognised by the 1820”s with the question of turning to commercial advantage the profuse growth of mulberry trees in Australia.

There had been a number of attempts to cultivate the trees especially for the breeding of silkworm, with the strongest advocate for the industry being Reginald Champ. Between 1881 and 1886 Reginald Champ had worked for a firm of raw silk merchants and in 1886 had gone to Canton to have a closer look at one of China”s well known resources. On three occasions, December 1888, May 1889 and July 1889, Champ wrote to Sir Henry Parkes, suggesting that the government encourage and facilitate the development of a silk industry in Australia. At the request of Sir Henry Parkes Champ then visited New Italy in October of 1889 to measure the level of interest amongst the settlers in pursuing a silk industry. He had been told that a loan of 1500 pounds would be made available to meet initial expenses.

The opportunity to establish a sericulture industry at new Italy was welcomed by the Italian settlers, to whom the establishment of a viable rural industry was paramount to the survival of the community. It was through thrift and resourcefulness that the New Italy settlers survived, and outside sources of income allowed them to support their livelihoods and families. The men were usually away from the settlement during the week, with timber and sugar cane being the two most important industries that helped support the settlers. By the late eighties the men were away from the settlement and their families on an average of six months a year. So it was with hope that the settlers enthusiastically embraced the idea of silk production at New Italy.

In September 1890, The Inspector General of Forests, J.E. Brown, accompanied Champ to New Italy to assess the suitability of the site for intensive breeding of silkworms. In separate reports both Champ and J.E. Brown concluded that soil-wise and human-wise sericulture could do very well at New Italy. The settlers then took matters into their own hands, addressing a petition to Parkes, assuring him of their willingness and ability. The then Italian Consul in Sydney, Dr. Morano, personally conveyed the petition to Sir Henry Parkes. Champ was appointed official advisor in early 1891 and arrived at the New Italy settlement in March. Life at the settlement was transformed as the breeding of silkworms became the major occupation of many. Greater areas of land were cleared with mulberry trees being planted 90 to the acre, everyone convinced that only mature trees were adequate to support the breeding of the silkworms.

However by early 1892 the community was delighted to see the silkworms doing well on the one year old saplings. The settlers once again showed their resourcefulness with silkworms being bred everywhere, sheds, kitchens to bedrooms, some even creating breeding shelves by stretching bushel bags over rough sapling frames. By June of 1891 sixteen families had received loans at 5% to help establish the silk industry at New Italy. However in October of 1891 the Parkes government was overturned and this resulted in a dwindling of government interest and participation in the sericulture venture at New Italy. A request that the government buy the settlement a recently imported reeling machine was made by Champ in 1892, but no response was received. Faced with a large number of cocoons ready for reeling Pezzutti and Martinuzzi used their ingenuity to devise and build their own reeling machine. In November of 1892 the Director of Agriculture F.S. Campbell visited New Italy to ascertain the success so far and the future of sericulture at New Italy.

On this visit he highly praised the reeling machine they had developed. This visit was in response to a petition to the Dibbs government the previous month asking for their continued support. Campbell was impressed by the results obtained and the enthusiasm for the venture in both the young and older generations at New Italy. He recommended the building of a filature, where silk reeling could be more professionally carried out. However this was not to occur, for 1893 was a bad year, with New South Wales experiencing a sever depression Meanwhile a fire ravaged and crippled the New Italy settlement, putting an end to sericulture as a large scale government sponsored venture. From this point silk making became a hobby for a few, the most notable being Giacomo Piccoli. Piccoli reportedly treasured his silkworms and would wear many garments of silk and even stuff his pillow with cut offs of silk. He won the first prize at the Sydney Exhibition in 1899 and at Milan in 1906.

<< (14) Educating the next generation of Australians

>> (17) Community Wall