WE DRANK IT LIKE TEA: WINE MAKING

Grapes were one of the few successful crops at New Italy, and family plots of grapevines spread across the landscape. Some families grew enough grapes to make between 300 and 400 gallons of wine a year.

Angelo Nardi, whose father Angelo was 13 when his family left Veneto, grew up at New Italy. He noted that drinking diluted wine was a tradition they carried on there, where “…if you drink it three times a day you get rid of it soon, enough.”

The Pezzuttis were one of the famed wine makers of the community, also owning an early wine shop in the settlement (the backdrop in the cafe).

In 1889, Luigi, Antonolli, established his popular tavern in the family’s two story home (the replica building in our grounds, now housing the Casa Vecchia Gift Shop). Woodburn men often frequented it, but with no license, Luigi was reluctantly closed down by police two years later.

New Italy Foodscape: Reflections from outside observers.

New Italy Foodscape: Reflections from outside observers.

This isolated community of non-English speaking Italians quickly became of interest to outsiders. From the time that the school was built at New Italy in 1885, a range of journalists, officials and other visitors provided comment on the settlement.

In the late 1880s, on his second visit to the settlement, colonial observer Frederick Clifford was highly pleased with the development of the settlement, observing that the ‘splendidly-tilled and cared for gardens, orchards, and vineyards met the eye on every side’. He noted that by sheer hard work and dedication the immigrants ‘induced the soil, which was of a cold and barren nature, to support and yield crops of grapes, lemons, citrons, apples, peaches, maize, oats, barley, lucerne, sugar-cane, onions, corn, cabbage, lettuce, peas, tobacco etc… Sweet potatoes appeared to grow spontaneously’

Wells were built from rocks and timber as there was no running water. Clifford commented: ‘Good water was procurable in any direction by sinking to a depth of 8-12 feet, there are no creeks’.

After the gruelling establishment of the settlement, the Italians followed their traditional peasant foodways to great effect for the next two decades. Fresh garden produce, foraging, preserved meat through salami making, poultry, polenta, bread and pasta provided a simple, nutritious and plentiful diet.

However, one of the worst droughts on record hit the North Coast in the first decades of the 1900s, where later observers found a much depleted landscape. By then, families had begun to pool enough resources to enable their younger people to leave the settlement for richer farmlands.

TO STOMP OR TO SQUEEZE: WINE MAKING

Many families sold grapes to outside markets while others retained their crops for their own wine making. Among Philip Pryor’s interviews with previous New Italy residents in the late 1970s, there were different memories regarding wine making. Dominic Marozin, whose father John had arrived from Orsago after the expeditioners and married Angela Nardi, remembered treading the grapes as a child in a wooden vat with his bare feet. Augusta Piccoli born Roder said that was never done in her family – they always squeezed the grapes.

Grape seed coffee

After the seeds are removed from the ‘must’, they are spread to be dried by the sun.

To make coffee, place the seeds on a baking tray and roast in an oven at 150°C to 170C for nine to eleven minutes. When they are cool, bring them finely in a coffee grinder and make the coffee in an espresso machine, or in a coffee plunger.

Taste test: The roasted and ground seeds have a divine aroma. However the coffee it makes is a bit insipid. So, no milk or sugar, and best taken with some red wine.

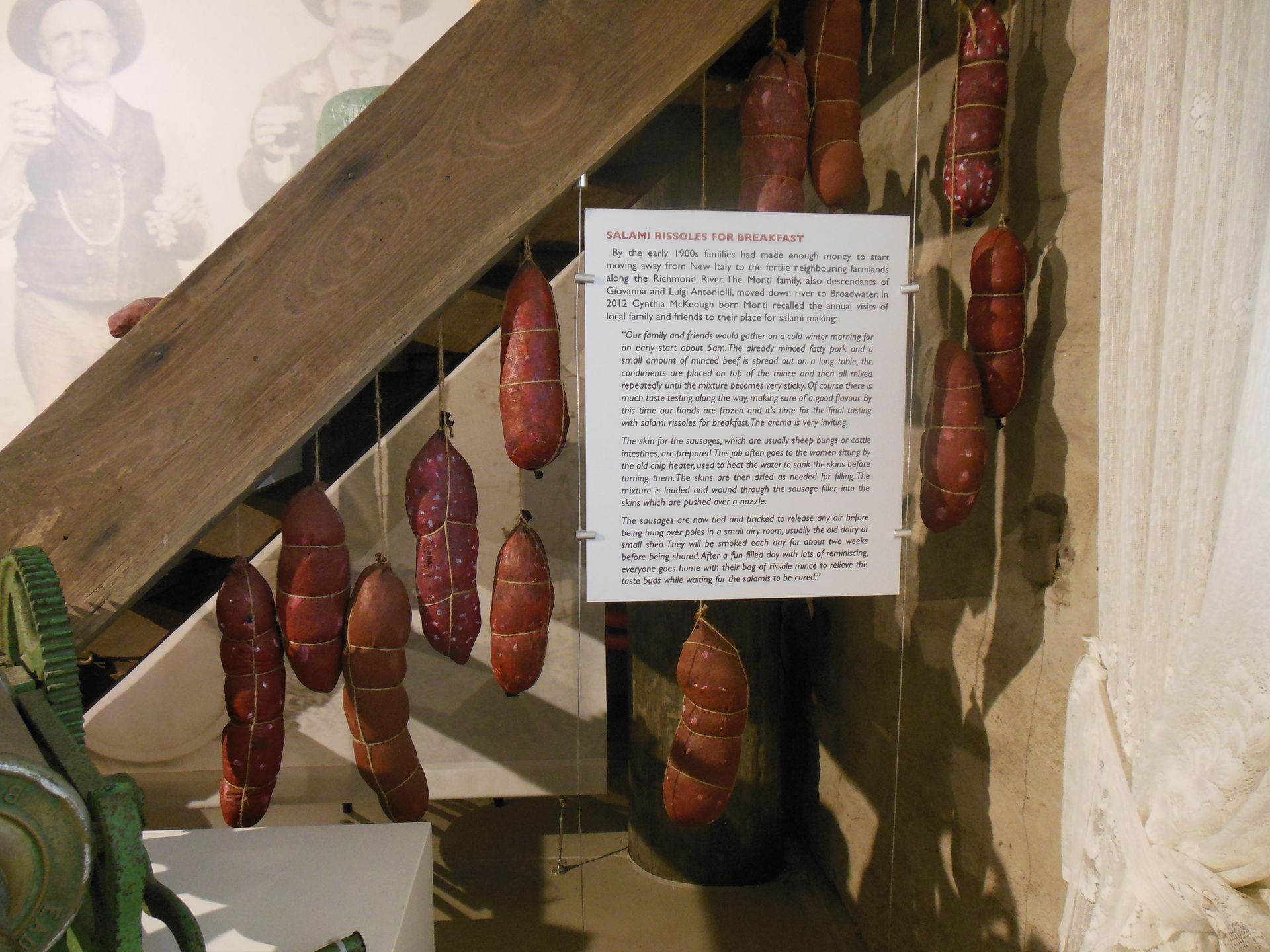

SALAMI MAKING AT NEW ITALY

Cured sausage consisting of fermented, air-dried meat has a long history across many cultures, supplementing meagre or inconsistent supplies of fresh meat. A strange and distasteful food for many British settlers of the region, New Italy families kept one or two pigs specifically to make salami. They were fed on the abundance of sweet potatoes and fattened with corn. Before the advent of the salami mincer, they chopped the meat with a squaring axe. In an interview with Tonie Pedrini in 1976, he described the process:

“The pork would be cut up first. A small amount would be put on a big chopping block. Then two men standing opposite each other across the block with squaring axes would start chopping. After a short period they would shift a quarter of a circle. The flesh would then be cut cross ways. This would go on until chopped fine enough. Meat [beef] was always cut smaller than pork.”

There was much deliberation over the taste, as it had to last for many months no matter what. Augusta Piccoli felt that while the introduction of the mincer saved time, it didn’t necessarily produce the best flavoured salami.

SALAMI RISSOLES FOR BREAKFAST

By the early 1900s families had made enough money to start moving away from New Italy to the fertile neighbouring farmlands along the Richmond River. The Monti family, also descendants of Giovanna and Luigi Antoniolli, moved down river to Broadwater. In 2012 Cynthia McKeough born Monti recalled the annual visits of local family and friends to their place for salami making:

“Our family and friends would gather on a cold winter morning for an early start about 5am. The already minced fatty pork and a small amount of minced beef is spread out on a long table, the condiments are placed on top of the mince and then all mixed repeatedly until the mixture becomes very sticky. Of course there is much taste testing along the way, making sure of a good flavour. By this time our hands are frozen and it’s time for the final tasting with salami rissoles for breakfast. The aroma is very inviting.

The skin for the sausages, which are usually sheep bungs or cattle intestines, are prepared. This job often goes to the women sitting by the old chip heater, used to heat the water to soak the skins before turning them. The skins are then dried as needed for filling. The mixture is loaded and wound through the sausage filler, into the skins which are pushed over a nozzle.

The sausages are now tied and pricked to release any air before being hung over poles in a small airy room, usually the old dairy or small shed. They will be smoked each day for about two weeks before being shared. After a fun filled day with lots of reminiscing, everyone goes home with their bag of rissole mince to relieve the taste buds while waiting for the salamis to be cured.”

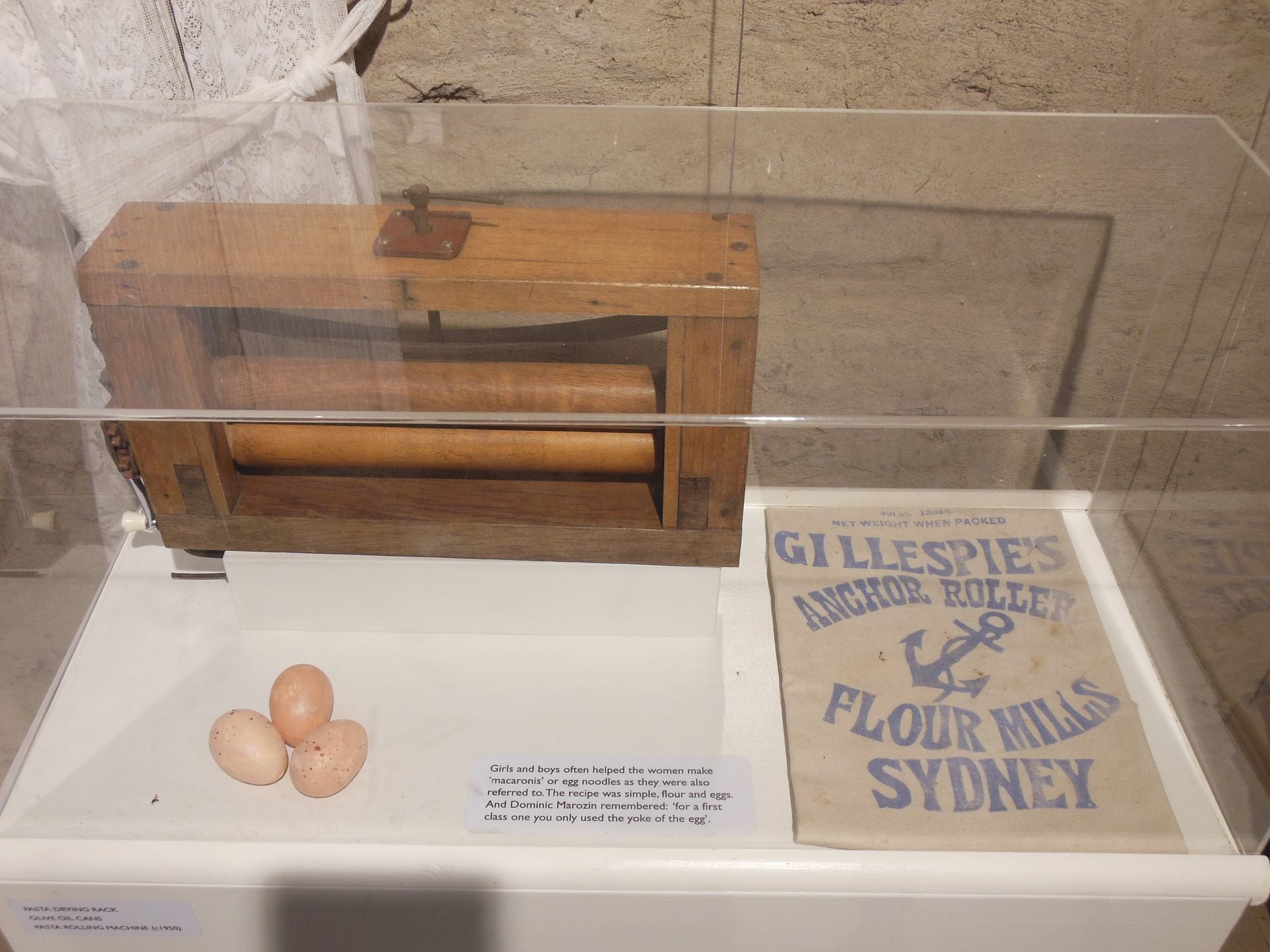

‘MACARONIS’: THE MAKING AND CHANGING OF PASTA

Pasta was one of the staple recipes the Italians brought with them from the old country and handed on to later generations. Beryl Haynes, of English parentage, met Raymond Antoniolli at a dance in Coraki, long after the Antoniollis had left New Italy. Raymond’s father Dominic (married to Margaretta born Guarischi of New Italy) was seven weeks old when his parents set sail on the Marquis de Rays expedition. Reflecting on married life, Beryl commented:

“Our family weren’t used to eating macaronis and Rayme’s mother taught me how to make it. Oh my goodness it was an all day job. You put eggs in it; you rolled it out and rolled it out and rolled it out.

Then you scrunched it all up. Then you rolled it out again, rolled it out, then you’d take it out and leave it in the sun for so long, then you’d bring it back in, scrunch it up again, roll it out, roll it out; take it back out in the sun. Then you’d cut it in strips and it was the most beautiful flavoured macaroni.

I remember that after Rayme’s mother taught me how to make the macaroni, one day I was home and Mum buys this macaroni in the packet. And I thought: ‘Oh cripes’ – all you did was dunk it in the boiling water for a few minutes and you had it! We were making spaghetti bolognaise, so I made it at home and Ray said, ‘Bon, what’s wrong with this macaroni? It’s not near as good as you always make.’ I said: ‘Mightn’t be as good – but I had it in five minutes not a whole day’”

Beryl’s story of marrying into an Italian Catholic family from New Italy is told in Salami, Shortbread and Parrot Pie.

Egg noodles

2 Eggs; 1 Cup flour to make stiff dough, Knead Roll out very thin; Cut into 2 inch strips;

Pile one on tap of another

Slice thinly and spread on paper to thoroughly dry before using

Note: No salt

Ref: Kate Hankinson born Capelin

Girls and boys often helped the women make ‘macaronis’ or egg noodles as they were also referred to. The recipe was simple, flour and eggs. And Dominic Marozin remembered: ‘for a first class one you only used the yolk of the egg’.

SALAMI, PASTA AND PARROT PIE: NEW ITALY FOOD

The northern Italian families who made their homes here from 1882 came from a culture where food, family and community were deeply intertwined.

A combination of grinding rural poverty, crop failure, political turmoil and high taxes had driven them from the Veneto region to risk everything for a better life. They embarked on the colonial expedition of a Frenchman, the Marqis de Rays, to the South West Pacific, But it was a dreadful scam. Their story is told inside the museum.

Eventually settling in this place, they brought their food traditions such as salami, pasta, wine making and a love of bitter greens. They also adjusted to their new circumstances and the different ingredients of their north coast surroundings. Here at New Italy the very poor soil, an unfamiliar climate and no immediate access to a water course made farming and cooking a great challenge.

They settled on land that previous colonists had shunned because of its barren agricultural prospects. Applying their intensive farming knowledge from their homeland, they persevered on their small selections. Remembering his family’s stories, Angelo Nardi commented: ‘It was remarkable that they could live there at all’.

As the community grew in later years to be joined by Scottish, English and Irish families, each group adapted some of their knowledge and preferences into different recipes. For example, salami recipes were revealed to selected non-Italian men, while Scottish and English cake and biscuit recipes were enjoyed amongst the women. You will find stories of such interactions in our book Salami, Shortbread and Parrot Pie: Stories of Multicultural New Italy.

Come through our display of solid cooking objects from the days of the settlement; find engaging stories and some interesting recipes. Grape-seed coffee for example? Best to try it with a glass of red wine.

PARROT PIE AND LAUGHING PIGEONS: WORKING WITH WHAT YOU’VE GOT

The New Italy settlers were able to order food staples such as olive oil from Anthony Hordern’s Emporium, Sydney. However, following a long tradition of the rural poor of Italy, they also foraged and hunted from the bushland around them. Eels, ducks and swans were eaten and when stretched kookaburras, known to them as laughing pigeons, also landed in the pot. Parrot pie was on the menu. No doubt the old bush joke rang true at New Italy: Boil the parrot with a stone in the pot. When the stone is soft the parrot will still need a bit more cooking.

<< (LU) Look Down, Look Up

>> (22) Nardi’s Dance Hall