Peter Blackwood’s Remembrance Day Speech

11-11-2023

We had a great turnout for our Remembrance Day service in the museum today.

The shift shop and café were closed during the service which was also attended by the staff. Our guests waited patiently for their coffees and joined us on the floor.

Peter Blackwood gave a very impassioned talk which can be listened to from the link at the top of this page.

Peter Blackwood gave a very impassioned talk which can be listened to from the link at the top of this page.

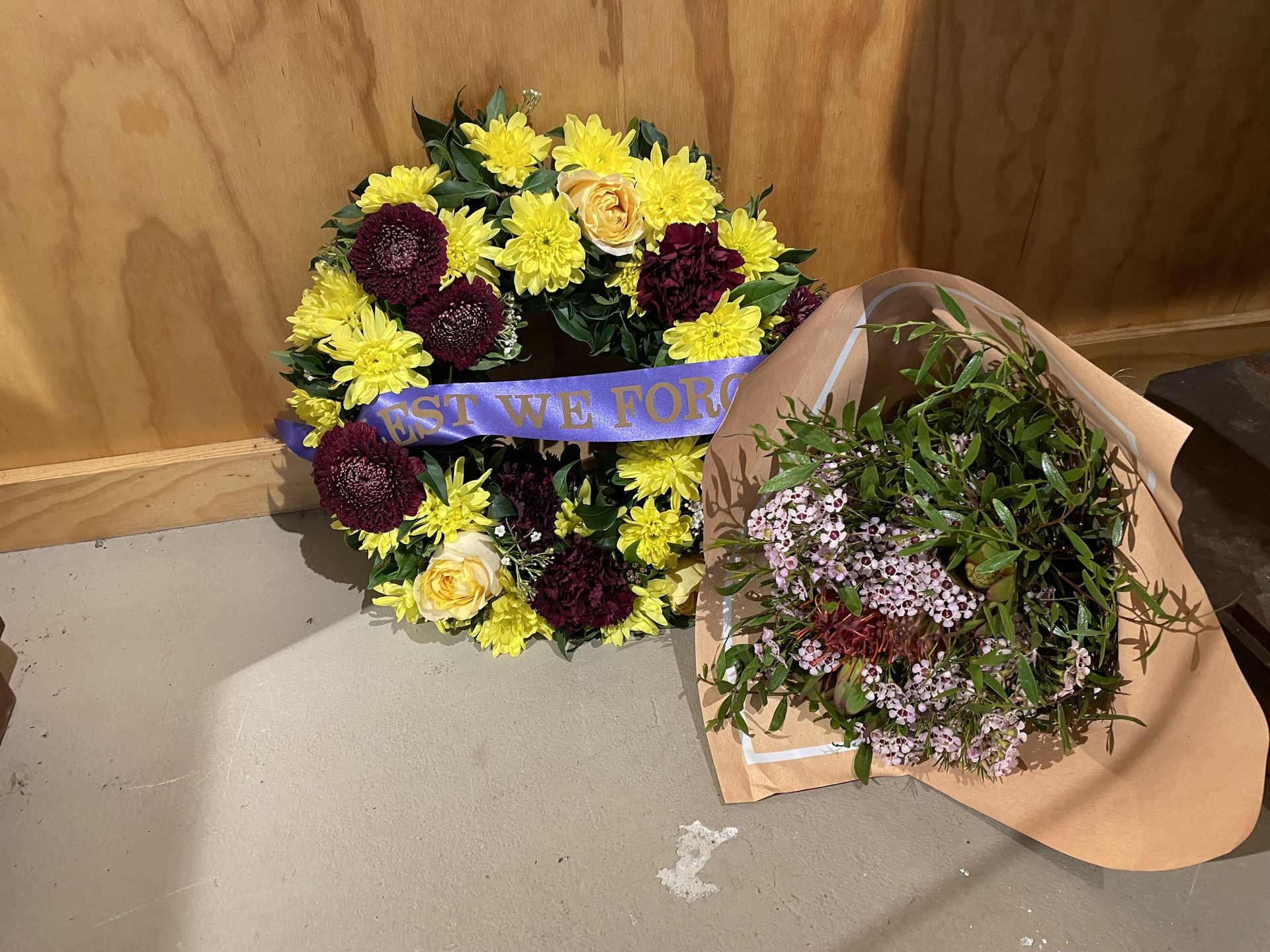

Flowers were placed by the museum and descendants of the Scarrabelotti’s on the Honour Roll also laid a bouquet .

After the service some rosemary was planted on the corner steps of the stage outside the pavilion.

Transcript of Peter Blackwoods Speech

Well, ladies and gentlemen, my name is Peter Blackwood.

I’m a member of the New Italy Museum Association.

And I’d like to thank you for joining us here this morning for this very simple Remembrance Day ceremony.

As you know, at this time, on this day, 105 years ago, the war to end all wars fizzled to a halt.

Unfortunately, that was not the case.

And today, we remember all those who served in all wars, men and women.

And in particular, we remember the 13 young men whose names are on the honour roll behind me.

Those young men were members of the families, the Italian families that settled here from 1882 onwards.

But by the time World War I broke out in 1914, many of those families had moved away simply because of the difficulties of maintaining a lifestyle on the poor land that is the area of New Italy.

Most of those young men were born here at New Italy or in Coraki or Woodburn.

I know of one who was born in Sydney. That’s Albert Caminiti, his older brother, John Caminiti, who was killed in action. He was born here at New Italy.

But their parents, her father being Rocco Caminiti, one of the men who induced the Italians to come and settle here. Rocco, in fact, was a sailor. He was no good as a farmer. And he soon found that out when he settled his family here. And after a short while, they moved back to Sydney where they established a very successful fishing operation.

More on that a bit later.

But those…

Caminiti brothers, the little fellow… I’ll call him a little fellow, Albert Caminiti.

He was 4’11 1⁄2, and he tried to enlist in the militia, but he was too short. But when the war broke out, the army was only too glad to welcome him in. So Albert went in.

He ended up in the 1st Battalion, Australian Infantry Battalion, and he was a bugler, stretcher-bearer.

And he saw service on the Western Front, some horrible service, being a stretcher-bearer.

And we’ve got a photo of Albert with the battalion band, and he was the bugler.

And the band are all this height, and Albert’s down here. He was quite a remarkable young man, though.

He survived the war and went on to go back into the family’s fishing business in Sydney.

And then when World War II broke out, he changed his name from Caminiti to Cam.

And at that time, the Cam family in Sydney had a very successful trawler, fishing trawler operation.

Eight of their trawlers, in fact, were commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy and saw service throughout the Second World War.

Two of those ships were sunk by the Japanese.

Unfortunately, Albert’s older brother, John Caminiti, who you see listed on the honour roll, he was killed in action. John was a bit older than Albert. He was 27 when he enlisted, and he was working in Sydney at the time as a fishmonger.

And at the time, he was living in a de facto relationship with a young widow who had two children.

And the story goes that he saw his younger brother go off to war, Albert.

He was inclined to go, but the decision to make him go was when he couldn’t decide what to do with regard to his relationship with his young de facto widow, whether to marry or not to marry.

The fight-or-flight syndrome cut in. He fought… He flew.

And the last his de facto saw of him was as he was marching down to Pyrmont to board a ship to head off to Europe. At the time, his young widow, and John didn’t know it at the time, was pregnant. Pregnant with their first child.

She had two daughters from her former marriage. And that child was born, John Caminiti, it was named.

And then they changed their name from Caminiti because the Caminiti family, being very strongly Catholic, was totally opposed to this concept of de facto relationships. And as you know, what is accepted now wasn’t acceptable then.

And the two parted company, the Caminiti family parted company, from Millicent, who was the young de facto widow. Millicent brought up her son, who then had another son.

And that other son, who we know now, tells us that Millicent, she worked and worked, brought up those three children and died at the ripe old age, I think it was 99.

But John, he went off, he joined… He was allocated to the 36th Infantry Battalion, saw service in France.

And in June 1917, the battalion was tasked with having to clear out the enemy, the German, from an area known as La Poterie, La Poterie Farm.

There was a series of trenches, and that was part of the battle for a much larger battle for the Messines Ridge, which the Australians eventually did secure.

John was with a party of soldiers from his company in his battalion that set off and, unfortunately, through an artillery barrage, he was killed. His battalion didn’t know he had actually been killed, though. He was listed initially as missing in action. And he stayed listed as missing in action until they had an inquiry several months later. And this was in June 1917 when he was killed, the 10th of June 1917.

What happened was, after the Australians went through and secured their position, they stayed there for two days, and then they were relieved by a New Zealand battalion.

And it was a young New Zealand soldier who found John’s body. He found his body. He looked through whatever papers he had on him, realised that his mother was his next of kin. And this young soldier, Private Kavanagh, from the Otago Battalion of the New Zealand Regiment, wrote to John’s mother.

Now, at the time, John’s mother didn’t know whether he’d been killed or not. They had received information that he was missing in action. Presume he is just wounded and he will be all right, the story went, until she got the letter from Private Kavanagh, this New Zealand soldier who, about two weeks after he’d found John’s body, wrote to his mother and told her.

It was an actual horrible shock, because Albert, his younger brother, the bugler in the 1st Battalion, he was trying to find out what had happened to his brother, because he’d heard about it as well. So he was in a bit of a state of great concern until he heard the story that filtered back through to John’s family, back to him in France. So he found out before the military actually told him that his brother had been killed.

The other young soldier that was killed there is Lorenzo Nardi. He was a gunner. Lorenzo was born here at New Italy and he was working on a farm nearby when he enlisted. He ended up a gunner in an artillery in the army. But the job he was given, was to be an ammunition runner. He would bring the ammunition from the rear to the guns.

A very, very dangerous occupation.

What they also had to do is defuse shells that had been landed, the German shells that had been landed around the Australian positions. So these gunners went in and had to get these shells and defuse them to make them safe.

In August 1917, Lorenzo, with one other gunner, was doing that when one of the shells exploded. The other gunner died instantly. Lorenzo was wounded and died the next day.

Now, the sad thing in that all these military units used to keep a daily diary. It was the task of the adjutant in each unit to keep a diary of what had actually happened that day. The incidence of death was so high, so great, that the daily diary for that unit, the day that Lorenzo Nardi and his mate were killed, the diary said, ‘nothing of significance happened’. Yet they had two of their gunners had been killed.

Nothing of significance.

And that, in fact, was similar in many of the other instances for those soldiers that served.

Of the 13, 11 were wounded.

Of the 13, two served with the Light Horse.

Young Fred Mazzer and John Tome, they served with the Light Horse in Egypt and Palestine.

The others all served, excuse me, in Europe.

So they were, of the 13, 11 were wounded, many quite seriously.

One I know in particular, and I had a brief association with this particular person, John Sanotti, whose name appears on the board. John Sanotti was known as Jack Sanotti, and whilst the Sanottis weren’t part of the families that came out on the ship and settled New Italy here, his mother, John’s mother, who was a Battistuzzi and who came out on the ship, did settle here.

So John, as he was known, he was known as Jack. I knew him in the 1950s as a kid in Kingscliff, up north of here. What happened was when Jack was… He wasn’t actually wounded, but he had… He suffered from mustard gas that was used on the soldiers in those days. And John had very difficult breathing conditions.

And he survived the war, came home, and he got married and ended up running the post office at Cudgen from about 1925 to 1940. Cudgen, up on the Tweed. Beautiful spot, where I went to school, in fact.

But in 1940, they moved down to Kingscliff and opened the general store, or ran the general store, and that’s where I knew him.

I used to go in to buy half a pound of biscuits or a bit of butter or whatever it is, as an errand from my mother.

And I remember Mr Sanotti. I didn’t even know he was Italian. That was such the way it was in those days.

Mr Sanotti, all I knew of Mr Sanotti, he was a very polite, very helpful gentleman wearing a lovely white apron that you would serve you in his shop.

And I had the pleasure of meeting his daughter, Beryl, here a number of years ago. Beryl said, I probably served you as well. But John, he became a very respected member of the community in Kingscliff.

Anyhow, we pause today to remember these people.

Each one has got a remarkable story.

So with that, our ceremony today will involve, I’ll shortly ask President of the New Italy Museum Association, Gail Williams, to lay a wreath.

We don’t have a bugler.

We won’t have a bugle call.

After the wreath laying, we’ll just observe a minute’s silence and then followed by the ode, and that will conclude the service.

So Gail, could I please ask you if you’d like to lay the wreath, please?

Ladies and gentlemen, if we could just observe a minute’s silence, please.

Thank you.

They shall not grow old, as we who are left grow old.

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

The going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them, lest we forget.

Thank you ladies and gentlemen.

Thank you very much.